Tools for Thinking

What's Generative AI really good for?

In this post, I share thoughts on writing a book in the age of generative AI. It includes notes informing Perspective Agents, to be published early next year. For more on technological forces changing our view on leadership and daily life, sign up here on Substack. Research notes and relevant news from Perspective Agents are also posted on Twitter/X.

Unlike staring at a blank page or facing writer's block, my book's creative challenge was different. Working with the Futures team at Weber Shadwick, I often see emerging technologies years before mainstream use. This project would be a race against the machine.

What if writing a book, this book, was a fool's errand? Judging from start-up demos seen in 2020, it became clear that AI-powered agents would soon transform how knowledge was constructed and interpreted. Instead of people holding the pen, machines would soon generate thoughts, ideas, and language that seemed human.

"Stunned" best describes how I felt using a GPT-powered writing agent for the first time. In 2021, I tested Copysmith to generate sample story ideas, ad headlines, and social media posts in seconds. Subsequent platforms wrote songs, stories, essays, and technical briefs. The idea that bots could write college essays or news articles at the time was still on the fringe.

We know the escalation story by now. When OpenAI released its GPT model in November 2022, more than 100 million people signed up. The scaling took less than 90 days. As we speak, genAI is infiltrating mainstream platforms, including Google Search and Docs, Microsoft Bing and Office, Adobe Firefly, and new Meta tools released earlier this week.

Whether we like it or not, intelligent agents will be embedded in the software we use. So, do writers need to worry? My read is thoughtful authors don't have to sweat the end of authorship.

As posted in Weber Shandwick's Media Genius newsletter, engines like ChatGPT aren't answer machines; they’re text-based prediction machines. By default, using them to automate creative output is misaligned. Good thinking relies on constant iteration of ideas. Good writing requires reflection informed by classic texts, research, and case studies. Most importantly, good work warrants wrestling with ideas in our minds, often in conversation with other people. All this happens before the creative act of writing starts.

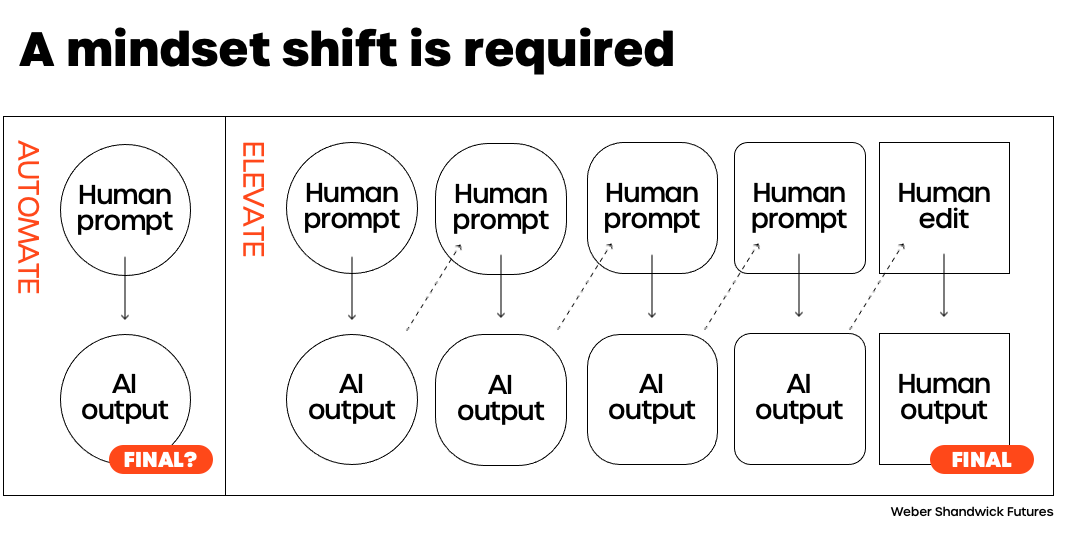

From a user standpoint, the idea of framing genAI as a writing calculator is misguided (as suggested by ‘AUTOMATE’ on the far left of the graph). When best used, it’s a resource to explore new thinking through a continuous exchange (as indicated in the ‘ELEVATE’ portion of the graphic). 👇

How does genAI alter the course for thinkers and writers in practice? From time spent using them, my view has shifted tremendously. More than tools to create content, generative AI can help deliver better thinking.

Let's break the view down further in the case of writing a book or newsletter.

IDEA GENERATION

Writing tools like ChatGPT and Sudowrite help to avoid staring at a blank page. They can propose story angles, outlines, and first drafts to get the juices flowing. Yet, for me, an under-the-radar app, AudioPen, is more valuable in originating versus responding to ideas.

The ideas don't come from the machine; they originate from raw thoughts. AudioPen synthesizes personal voice notes with a GPT model, turning audio messages into coherent statements. For this newsletter, Audiopen helped me create a starter premise from a few disparate comments that generated this. 👇

RESEARCH

The painful process of accessing relevant academic and technical research is made easier by apps like Consensus and ChatPDF. Consensus is a search engine that extracts and distills data from scientific research. As seen below, Consensus returns the most relevant results, and, through the synthesis command in the upper left, can use genAI to summarize findings. 👇

While I don’t use Consensus’ GPT function, I pair what it returns with ChatPDF. This extracts meaning from previously locked journal articles, books, research papers, essays, and legal contracts. ChatPDF speeds up finding high-signal insight within papers, allowing you to ask questions about reports as if talking to the authors. It can distill findings into key points, help you press for clarity, and expand your interpretation beyond what's in the file.

In the two instances below, I pulled reports from Consensus and dropped them into ChatPDF. The first, while seemingly on point, didn’t fit the premise of this article. From the PDF chat, the language model distilled the findings around an academic model (a Qualitative Model for Creativity (CCQ), not how generative models aid the creative process. The chat indicated there wasn’t a need to read it in full. 👇

This second research note from the University of Nebraska confirmed my working hypothesis: That genAI is a creative aid and shouldn’t be relied on for delivering the fittest answers. While I didn’t cite research findings in this newsletter, the exchange did validate my line of thinking.👇

INTERPRETATION

My research recall radically changed with Readwise. It aggregates your annotations into one place, making it easy to review notes and highlights. Two features change learning and interpretation of notes you save. The first is Ghostreader, a GPT-3 powered engine that, like Consensus, allows you to interact with archived content. Ghostreader helps gain clarity by looking up terms, summarizing articles, creating flashcards, and translating the content if necessary.

Readwise also uses a scientific process called “spaced repetition.” It’s a memory technique that involves recalling information at optimal spacing intervals until the information is learned. Readwise builds space repetition into its UX. It resurfaces your annotations, bringing to the fore not just learning but potential serendipity. As shown below, daily emails and apps surface notes through a newsfeed. The circular nature keeps relevant ideas in mind by resurfacing potentially relevant thoughts (for instance, I disagree with Dr. Kissenger’s statement below). 👇

IDEA BANKING

To file ideas, notes, and annotations, I started with Scrivener and then migrated to Google Docs. Ultimately, Obsidian became the primary repository. It’s a place for organizing notes that inform my book’s manuscript and newsletter development. While some use Obsidian for content summation with GPT plug-ins, my Obsidian vault is for storing, sorting, and visualizing notes. The connections seen in graph mode were invaluable creating novel outlines and starter references to work from. 👇

DRAFTING

Okay, so if that's the process behind thinking up stuff, how do tools help bring the stuff to life in a draft?

While genAI tools were transformational in research, I firmly believe people still hold the pen and shouldn’t give it up anytime soon.

For experimental writing, I primarily tested ChatGPT, Sudowrite, and the genAI plug-ins for Google Docs. I used them to shape chapter outlines, generate headlines, and test copy variations. They were okay at best. You can get by if you want to write generic, machine-like content with occasional flair, anecdotes, or metaphors. But to originate thoughts, draw connections between stories, and shape a narrative that grabs people, it’s still on you. Having spent hours with these tools as a sidekick, creating compelling, personally informed narratives through a machine was a non-starter.

There’s an upside to working with them once you flip your view. It's assumed that when using genAI tools, we prompt machines for answers. I found the opposite to find real value. Machine replies prompt me to think more expansively, accurately, and convincingly.

Lex, an AI-powered editorial assistant, is a case in point. Lex uses GPT-3 to give users structural, grammar, and style improvements. The most valuable –and uncanny capability– is its mode as an executive editor. It evaluates story ideas, the quality of the article drafts, headline suggestions, and narrative flow. If you ask Lex for feedback to improve a piece of writing, it’s pretty good at following logic, evidence, takeaways, and gaps. Here’s a screen grab of Lex analyzing this post. 👇

STYLE AND FACT-CHECKING

If Lex is an executive editor, embedded agents like Grammarly are solid proofreaders. But again, they're far from foolproof. I’ve found Grammarly, Google Docs, and Word each flag different style errors, knots, and typos in a book-length text. Final proofs still sit in human hands.

As for fact-checking, I found one AI to be surprisingly helpful. While you shouldn’t trust the accuracy that comes from engines like ChatGPT, Perplexity is a good tool to vet content. It differs from other engines in that it cites sources for its answers. It prompts users to go deeper into the subject matter and sources to vet the origins and credibility of the content. 👇

A GOLDEN AGE FOR WRITERS?

A final note on the question of authorship in the age of genAI. Prompts to get the most from these machines are the domain of writers. The pre-eminent science and technology reporter Steven Johnson recently said, “You have to be able to craft sentences and think about what’s in the virtual mind of the entity you’re trying to persuade to do something. Right now, we’re in this weird period. It’s a wonderful time to be a writer.”

Whether prompting machines for insight or using them to refine lines of text, I see where Johnson is coming from. Just be careful not to cede the real stuff of thought to our AI co-pilots.

My Lex editor suggested I include opposing views in the post. I’m curious if you see it differently. What genAI tools do you use, and what have you learned? Share your takes or tips here in the chat.

Very interesting. I use chat gpt 4, and it's been useless for generating ideas or for sources, but it's incredible for editing.

Most of what I write about is not digitized, but I can see that it is not an original thinker. Given a prompt like "come up with an ad for cleaning", it does a terrible job.

https://ishayirashashem.substack.com/p/tv-commercials-produced-by-iyh

This is hugely practical, thanks for sharing this, Chris!