On a recent episode of The Ezra Klein Show, President Biden's lead AI advisor, Ben Buchanan, delivered his points with unusual urgency. Klein himself noted the interview's significance: "I've been having this strange experience where person after person, independent of each other, from AI labs, from government, have been coming to me and saying, 'it's about to happen.'"

The show's title is ominous: The Government Knows AGI is Coming. Klein and Buchanan describe this superintelligence storm as an "event horizon," a point of no return, a reality fundamentally different before and after.

They go on to speak of AI as an arms race, a national security challenge. Buchanan then pivots to near and personal threats. By the end of the year, he thinks more machines will write code and more companies will stop hiring. Across the board, he warns, we're not prepared because "it's not clear what it would mean to prepare."

Buchanan calls incumbents "constrained for thinking unusually." Translation: governments, corporations, universities, and religious institutions are ill-suited to help us see and adapt to the storm. Without interventions, anticipatory myopia may very well lead to systemic paralysis. It’s worth your time to listen to it in full.

Where are the artists?

So, is there a way to visualize and prepare for the break? If Klein and Buchanan are right about AGI, are we doomed to a future of optimization, reductionism, and risk?

We should look beyond the media, technologists, and policymakers for answers to profound questions. Artists can be our guides. Those who’ve explored human-machine relationships for decades—and those deep in creating with AI now—offer essential insights overlooked when contemplating the future.

For artists, this isn't new territory. Human-machine creations, dating back to the 1950s and 1960s, offer a powerful counterpoint to complete preparation blindness that Buchanan warns about today. For a sense of direction, the cybernetics arts movement from this period suggests:

Technology is a creative amplifier (not a reductionist tool). Leading figures of this period—Nicolas Schöffer, Nam June Paik, and Lillian Schwartz—modeled relationships with machines that transcended utilitarian thinking. Their work demonstrated how outcomes emerge organically—suggesting new methods for learning, creation, and building. Unlike the deterministic paradigms that dominated technical fields, these artists embraced surprise, chance, and feedback as essential creative elements.

Machines can be partners and acquaintances (rather than deterministic systems). The cybernetic art movement centered on open-ended creation over technological control or productivity. A distinct class of artists proliferated across continents and disciplines. Post World War II, visionaries like Vera Molnár (France), Roy Ascott (UK), the Vasulkas (Iceland/Czech Republic), and Charles Csuri (USA) pushed the boundaries of computer-generated creativity. Where technological determinism says that technology shapes society in predictable, inevitable ways, they proved people can redirect advancements through interventions and reimagination.

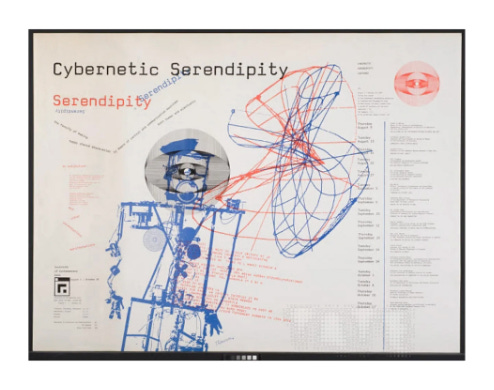

New explorations surface new questions (rather than reverting to convention). Pioneering work featured in exhibitions like Cybernetic Serendipity (ICA, London) and Machines as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age (MOMA, New York) intentionally upended assumptions. They demonstrated that social impact stems not from inherent properties of the technology but from the context and creative interpretation when deploying it.

In the right hands, technology elevates creativity (as opposed to automating it). Artistic pioneers showed that machines need not constrain human agency but can expand creative horizons. They exhibited that technology's impact is not fixed but shaped by how we conceptualize and deploy it.

A Visionary Thread

One public exhibition from the 1960s shows the ingenuity and scale of mid-century cybernetic art—a case in future potential.

Now, picture how radical (even ludicrous) this must have been. An up-and-coming art curator appears on a sepia-toned film recording. Jasia Reichardt introduces her new project, Cybernetic Serendipity, which was three years in the making. Talking about it, she rightfully conveys belief and disbelief simultaneously.

It’s a big swing. Her exhibition is the first visible exploration of machine-generated art for the general public. It allows visitors to experience computational aesthetics and production methods. She forces visitors to reconsider who or what a creative agent could be.

According to Reichardt, a wholly new, experiential perspective had crystallized. Computers now interacted with people, drew graphics, rendered portraits, and wrote haikus (remarkable, considering this was the 1960s). Her program would elevate these mechanical wonders into the mainstream.

While preparing for the exhibition, Reichardt regularly consulted a journal called Computers and Automation, the world's first computer magazine. In its pages, several contributors to Cybernetic Serendipity were discovered, including Bela Julesz, Michael Noll, Frieder Nake, and Georg Nees—vanguards of computer-generated graphics and algorithmic art.

They institutionalized new forms and works that blended art and science. The subject (what the machine was) became the source (what the machine could do).

Featured in her introductory remarks, Reichardt discovered, "When one goes to an art exhibition, or an exhibition involving poetry or music, we think that the people who have composed the music or produced the images or written the poetry are artists, poets, or composers. In this exhibition, this is not true."

Cybernetic Serendipity featured works from over 130 contributors, including computer scientists, engineers, artists, composers, and poets. Notable participants included Nam June Paik, John Cage, and researchers from Bell Labs’ Experiments in Art and Technology group (E.A.T).

It immersed visitors in computer-generated graphics, sculpture, music, and poems. People wandered through interactive cybernetic environments, engaged with remote-control robots, and witnessed painting machines creating artwork in real time.

A pixelated, computer-rendered image of Norbert Wiener, the father of cybernetics, greeted them.

Then came Gordon Pask's "Colloquy of Mobiles," a hanging system of rotating fiberglass forms communicated through light and sound. Visitors interacted serendipitously with the mobiles, becoming part of the artwork's feedback loop—human and machine in dialogue.

Interaction between visitors and machines wasn't limited to Pask's installation alone. Various works explored different facets of technological conversation. Edward Ihnatowicz's "SAM" (Sound Activated Mobile) took feedback loops even further. The flower-like sculpture turned toward sounds, tracking movement with an almost lifelike responsiveness that blurred the mechanical and organic lines.

The exhibition provoked a mix of astonishment and bewilderment.

The Observer remarked, "Is everything or anything here art—and if not, why not? We all benefit by asking ourselves this kind of question." The Sunday Times declared that "'Cybernetic Serendipity' provokes, in its implications, it is as different from an everyday' art exhibition' as a major operation from a manicure." The Evening News prophetically announced, "The Industrial Revolution provided the machine age. With the computer comes machine-made art."

The exhibition attracted over 60,000 visitors in just three months—an impressive number for an art exhibition in 1968. The strange new fusion of art and technology raised questions that resonate even more powerfully today:

What is authorship when machines participate in creation?

How do we understand creativity when it emerges from code and circuits?

What new forms arise when machines are the subject and source?

What defines the essence of human imagination when technological creations mirror our capacities?

Rather than marking the end of human expression, Cybernetic Serendipity proposed a profound expansion. New questions emerged, assumptions changed, and along with it, new means to understand art, technology, and creativity.

As we approach an "event horizon," economic competitiveness, technological supremacy, and fundamental natures of human agency are in question.

If we overlook artistic perspectives—with their emphasis on emergence, collaboration, and meaning-making—we risk directing AI systems to optimize us and diminish immeasurable qualities that define our lives.

That’s why we must follow the artists. Marshall McLuhan reminded us that they—not machines or people who make them—are the antennae of the human race.

It’s not a perfect parallel, but as technology has made things easier for entrepreneurs, the real variables have become clearer.

Before e-commerce, selling merch like t-shirts and hoodies required a major financial commitment. You still had to create great designs that people wanted—and market them in a way that made people want to buy.

E-commerce lowered the overhead and made launching an online store easier. But you still had to create great designs that people wanted—and market them in a way that made people want to buy.

Print-on-demand platforms eliminated most of the financial risk, making it easier than ever to offer a wide range of products. Yet, you still had to create great designs that people wanted—and market them in a way that made people want to buy.

Now, AI tools have made generating eye-catching designs even simpler.

But you still have to market them in a way that makes people want to buy.

How does this relate to the artist and AI? People will always buy great art/designs from people that they connect with. Artists who use AI to become better artists will thrive.

And how would AI ever replace or replicate marketing?

Love this. Couldn't agree more!